Formal interagency security coordination mechanisms, such as INSO and GISF, provide analytical products, guidance, forums for discussion and training opportunities. Where no formal mechanisms exist, informal networks frequently emerge for sharing information and advice, often using online or SMS-based platforms.

Security collaboration and coordination between the UN and international NGOs functions in a framework called Saving Lives Together (SLT). SLT’s goal is to enhance informed decision-making and manage risks through shared information and resources. Implementation has however been slow, and there is limited awareness of SLT at the country level.

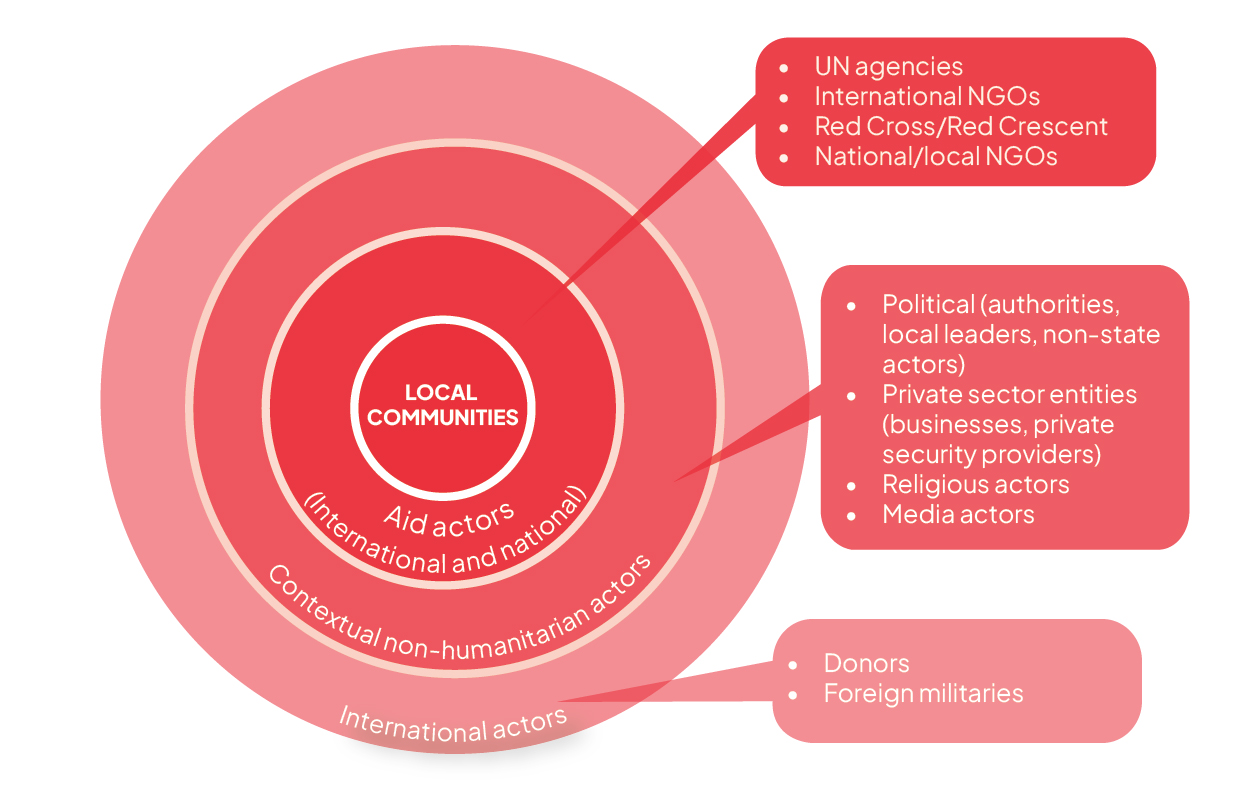

Humanitarian organisations also interact with private security companies. Although the use of armed protection by private security providers is uncommon, humanitarian organisations have engaged these providers for unarmed guarding and other support services, including analytical work. When employing private security providers, organisations must carefully consider who they hire and how they will be employed. Key considerations include ethical standards, compliance with international law and adherence to codes of conduct, as well as potential affiliations with political or military actors. Resources like those provided by International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA) can support organisations in conducting due diligence.

Humanitarian organisations must also liaise with authorities on operational and security-related matters. Continuous exchange with government counterparts, including foreign authorities and sub-state actors, is often vital to secure humanitarian action and meet duty of care obligations. It may be advisable to exercise caution when engaging with government counterparts, particularly in contexts where authorities may be hostile to aid efforts. In conflict zones where non-state armed groups control territory, humanitarian organisations may need to establish dialogue with these actors to negotiate access and ensure the security of their personnel. Engagement with non-state armed actors requires careful preparation, including an understanding of their motivations, political affiliations and relationships with other conflict parties, as well as local communities.

Coordination between the military and humanitarian actors is often vital to facilitate safe humanitarian action, but engagement can be challenging. Several mechanisms exist to guide and support civil–military coordination. The Humanitarian Notification System for Deconfliction (HNS4D) mechanism aims to enhance the security of humanitarian operations by notifying military actors about the locations of humanitarian facilities, movements and activities in conflict zones.

A wide range of other actors, including businesses, community groups and local civil society organisations, may also be present in the operational context and can provide valuable insights and support. It is important for humanitarian organisations to consider how their interventions and security decisions may affect these actors.